Veritas is Latin for “truth.” The articles found here are intent on providing truth in knowledge, guidance, information, leadership, and inspiration. Many will be co-written with other great trainers whose voices can move us towards great achievements.

Against the Current

September 24, 2014

On a typical warm summer's day in August, I joined a couple of dozen friends on a canoe trip down the Fox River near Ottawa, Illinois. After arriving at our starting point, we pushed off nearly twenty canoes for a good day's journey towards our destination further downstream. Packed with food, drink, and music, we had prepared for an enjoyable time of fellowship.

With a choice to either make solo trips down river or sojourn bound together, we opted for a leisurely trip in tandem. The former would cause rapid progress towards the end of the trip while the latter gave time to enjoy the company, the weather, and the scenery. The mission for the day, after all, was to take it easy.

With eight canoes forming a barge, the Fox River's current carried the lumbering mass downstream at a slow, steady drift. No worries. No cares. Life was easy. No effort proved to be necessary as umber, rust, and beige bluffs ambled past like quiet, giant beasts. Country music, laughter, and storytelling filled the air, our voices, and our hearts. Five hours to float downstream towards a meal of catfish, chicken, and plenty of complementary side dishes.

Approaching the area approximately a half mile from our destination, the current slowed dramatically - practically to a stop. In fact, it seemed an opposing current now impeded our travels. Our coasting carried us only so far. To reach our objective - and a fantastic supper, placing oars in the water became a necessity. Separating the canoes and paddling with strong, coordinated effort, we pushed against the current. Strength, determination, and coordination moved some outriggers faster than others and reached the target quicker. But to do so required great effort.

If you think adventure is dangerous, try routine. It's lethal.

In our personal lives and as leaders, we are constantly presented choices in how we reach our destinations - how we achieve our goals, our objectives. We can opt for taking it easy and letting the currents take us wherever we are going. But going with the flow will, indeed, only carry us so far. Nothing worth achieving comes without great effort.

Destinations worth reaching require that effort, and frequently against the current - sometimes very strong ones. Strength, perseverance, and courage all factor into our ability to go against the mainstream to achieve goals - whether those we hold for ourselves or for our organizations. Sometimes that opposing current is within us - old habits, doubt, fear of change, popular belief. Other times the similar factors are affecting our organization's ability to reach new landing-place. The "we've always done it this way" syndrome, the fear of "different" or "new," and lack of faith make it easy for followers to prefer the steady, easy pace of floating with the current - with what is known.

"Safe" - or going with the flow - only gets us to a point of stagnation. Pushing against the current allows us to reach places we never otherwise would be.

Come on. Put your oar in the water. And push.

The Power of Will: Lessons from Jared Reston's Fight

November 21, 2012

By Timothy Janowick

“It is not the will to win, but the will to prepare to win that makes the difference.”

- Bear Bryant

After surviving a deadly encounter with a thief, Jacksonville Police Officer Jared Reston understands the difference between living and dying is his will to prepare for the fight. Officer Reston spoke to police officers at the annual Illinois Tactical Officers Association Conference this past week, recounting his engagement with thief-turned-killer, Joel Abner, and the lessons learned from this harrowing incident.

Not A Typical Off-Duty Overtime Detail

On the evening of January 26, 2008, Reston and his partner were working an off-duty assignment at a local shopping mall. Security notified the officers of two offenders committing a retail theft. One of the thieves was physically fighting with the loss prevention officers and the second offender fled on foot.

When Reston arrived in the area, he observed the fleeing offender, Joel Abner, standing at a bus stop near the mall. Upon seeing Officer Reston, Abner took flight. Reston, a strong and very physically fit officer, gave chase. The foot pursuit started with the westward crossing of a six-lane roadway filled with many cars in the early evening hour. Reston describes his foot pursuits as a game where he pushes the offender by hanging back a bit and letting the suspects tire.

Abner rounded the corner of a building and headed south through a parking lot. As he reached the end of the lot, he turned west again and began to walk parallel to the roadway. Reston quickly catches up with the suspect as he nears a drained retention basin.

“Stop, it’s the police. It is not mall security you’re messing with,” ordered Reston as he drew a TASER and pointed it towards Abner’s back. Abner raised his arms, turned, and started to run again. Reston pulls the TASER’s trigger and waits for the muscular disruption to take place so he can take custody of Abner.

But the TASER fails with a complete failure of the weapon to discharge. Reston quickly re-holsters the TASER and realizes he will need to engage in hand-to-hand combat with Abner. Reston resume the chase and as he catches up to Abner, Abner’s back is to him.

Violence of Action in 6 Seconds

Reston places a hand on Abner’s shoulder. Abner spins rapidly and assumes a fighting position. Reston recognizes Abner’s aggressive behavior and punched him in the face, followed by a quick head-butt in an effort to take Abner to the ground. Suddenly, Abner produces a pistol stolen during a burglary to a gun store 15 years earlier. Reston has no idea the dynamics of this fight have taken a serious and deadly turn.

The first shot strikes Reston in the chin, knocking him to the ground. Believing Abner caught him with a good punch, Reston thinks to himself he needs to amp up his actions in response to Abner’s fight. Then he comes to understand the sobering reality and gravity of the situation as he notices his teeth are laying back in his mouth and his jaw has collapsed as a result of the explosive force of the bullet’s entry into his body. The force caused teeth to fly from his mouth, shredding his uniform shirt and impacting his ballistic vest.

Reston’s radio calls for help are unintelligible. His partner is running in his direction and can hear the gunshots. The partner radios what is occurring as the gunfire fills the background of the radio traffic.

Abner stands over Reston, continuing to shoot the officer. With wounds to his jaw and elsewhere, Reston becomes angry; Abner is attempting to murder him. Abner begins to walk away, shooting back at Reston. “He was going to just walk away like nothing happened,” recalled Reston. “My will to win kicked in.”

Convinced he would not let Abner win, Reston moves to his back, raising his torso, draws his Glock 22 pisto,l and aims for Abner. Abner notices this movement and closes the distance, firing at Reston in an effort to finish him off.

As Reston rises to engage in the fight for his life, he feels the piercing pain in his buttocks and knees - he now knew he has been hit more than he thought. Reston began shooting Abner. Even though Abner was impacted by the .40 caliber ammunition, he continued the charge towards Reston, circling him as he lay in the basin. Reston describes his efforts to fire upon Abner as being “like trying to hit someone with water from a hose and he’s trying to avoid the stream of water.” Reston sees Abner wince as rounds tear into his body, but Abner continues advancing directly at Reston, firing repeatedly in an effort to end Reston’s life.

Reston makes it to his knees, continuing to fire. The impacts of the bullets on Abner’s body cause him to fall on top of Reston and the men drop to the ground together. Reston must win this fight and he is forced to end the attack in a very close and direct way: Reston places his pistol at Abner’s head and fires three rounds.

The Aftermath

To create distance and cover, Reston uses his feet to roll Abner into a culvert. Reston pushes himself away and maintains cover until his partner arrives. Upon arriving, he crosses over Reston’s body, searching for the offender. Reston indicates Abner’s location and his partner checks Abner for signs of life. Abner is dead.

The focus is now on Reston and his care. In addition to the gunshot wounds in his jaw and hips, Reston has two gunshot wounds in his thigh and three rounds impacted his ballistic vest. Medics are summoned to the scene and buddy care begins. Another officer arrives on scene, grabs Reston’s hand, and offers words of hope: “You’re going to be alright.”

He then looks up and says, “Where’s rescue? He’s going to die.”

An autopsy of Abner indicated Reston’s rounds struck him in a number of places. Two non-fatal rounds entered his center off mass in the right abdominal area and remain in the body. Two of the contact wounds on Abner’s head only caused massive structural damage - they were non-fatal. Two wounds proved fatal: one round entered his back, pierced a lung, and traveled upwards through the body into the neck severing the vertebral artery; and the third contact head shot.

Lessons from the Fight

Officer Jared Reston and police officers everywhere learned valuable lessons as a result of this deadly encounter with Joel Abner.

First and foremost, Reston’s personal and professional philosophy are worthy of emulation by all law enforcement officers. He takes training seriously, and he credits the training as “what helped me win that fight that day.”

“Seek out additional training,” Reston advised the officers in attendance at ITOA. “Set time aside to go to the range. Spend some of your own money on training. Train: do not just go through the motions. Ramp it up.

If you are worried about getting sued, you are behind the curve. Know your agency’s use of force policies and your state’s statutes on use of force. When you know you are righteous, everything will come much quicker.”

Mindset was key to Reston’s survival. “Mindset is about getting the job done professionally. Your mindset must be honed and trained.” Mindsets are not just about surviving the fight, but winning it. Winning minds mentally rehearse the event of being shot and how you will react prior to having such an event. Reston prepared himself for the unspeakable violence he would need to do to those who wished to do him harm. Mental preparation is key to winning. Reston encourages officers to mentally rehearse every scenario they can imagine.

“My ballistic vest saved me that day. To not wear body armor is inconsiderate, selfish, and lazy. It sucks, but that suck is our job. Think about family, friends, and other people in your agency. Put it on.” Reston stated with firm conviction. Always wear body armor (one of the tenets of Below 100). Wearing body armor increases an officers chances of surviving a gunshot to the torso threefold.

Reston learned important points about using an electronic control device such as his TASER:

- •Be prepared for any weapon to fail. What are your contingencies for a weapon failure? Have you trained and tested your contingencies?

- •Train to re-holster your TASER because windows of opportunity open and close quickly. Fumbling through an unpracticed action takes valuable time. Practice re-holstering all your weapon systems.

Officer Reston reminds us mental preparation does not just include rehearsing what we will do in our own deadly force situations, but also how we will help other’s in the most critical moments. “Don’t be that guy,” he warned ITOA attendees. That Guy is the officer who told him he would be okay, then asks where rescue was.

Finally, Reston recalled the lessons he learned as he fired upon Abner. “I focused on my front sight. I never had a perfect sight picture, but I placed my front sight on Abner. I saw the suspect wincing in reaction to being hit. I had center of mass hits on the suspect, but he did not go down.” Most gunshot wounds are survivable; suspects will be struck and keep coming.

“I always took training seriously; it is what helped me win that day,” Reston commented.

How seriously do you take your training? How do you prepare yourself beyond your agency’s training program? What personal and professional philosophy will you adopt to answer life’s most important question: What’s Important Now? How will you W.I.N.?

Bear Bryant said, “It’s not the will to win, but the will to prepare to win that makes the difference.”

Just ask Jared Reston.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ArDRg5SkuT0

Five Lessons in Media Relations

Saturday, October 6, 2012

By Timothy Janowick

When the media comes calling asking questions, are you prepared to provide the answers? A few lessons I learned about interacting with news reporters created the difference between a good story getting lost as a result lame preparation and a great story being related to the public by reporters.

Over the last nine months, the community where I am employed experienced a number of burglaries. Our investigators, stymied for several months without viable leads, developed suspect information an began surveillance. After several weeks, the investigators swopped in, made arrests, and recovered nearly a thousand individual stolen items tallying in the tens of thousands of dollars. The capture of the burglars proved important for three reasons: a crime spree ended and the victims would be able to recover their stolen property, the public could be reminded of risk management practices to mitigate the chance of becoming victimized by criminals, and the closure of the case presented an opportunity to relate a story of good police work.

Wanting to make sure people heard the story of our investigators, I crafted and issued a press release expecting the story to appear in the newspapers the next day. I did not, however, expect the news media - newspapers, radio, and television - to promote the story at greater lengths. As a result, I conducted interviews with a local news radio station looking for soundbites to enhance their reporting of the story, several newspaper reporters seeking additional and more detailed information, and two television news crews seeking to put together a great package story about these events.

A novice in media relations, every interaction provides an opportunity for me to learn and develop my communication skills with reporters. Here are a few takeaways I have after my experience this week:

- Know your subject matter. Prior to issuing the press release or speaking with the radio and television stations, I interviewed the investigators and their supervisors to develop talking points and determine what information they did not want released. I did not want to be left without an answer to a reporter’s question.

- Create a package. Roseann Tellez, a CBS Channel 2 news anchor, sought a package and we delivered by providing access to department representatives for interviews, access to the recovered stolen items to record B-roll footage for use in the story, and locating a victim willing to talk about their experience on camera. Packages make the story more interesting and complete when aired - and make reporters happy.

- Provide soundbites, not monologues. The task of providing soundbites is trickier than one might think. Considering I am used to teaching in front of large groups, I found myself engaging in long responses at times. Keep the answers short; the reporters are crafting a story whose airtime will be a mere 90 to 120 seconds. The reporters are looking for snippets to weave into the story they will tell.

- Expect different reporting styles and adjust accordingly. NBC Channel 5 news reporter Phil Rogers approached the process of constructing a story with a different perspective and process. I appreciated the differences in the methods used by Tellez and Rogers. Tellez asked questions in spurts with different camera angles and backgrounds as she built her story. Rogers asked a series of successive questions in one shoot of the interview. Just as we have different tactics to apply to the same situation, the reporters also have different tactics to reporting the same story. Adjusting accordingly created a cooperative environment between the reporters and me.

- Build relationships. In the process of building the story for the news, I realized this was not just about “our story” nor was it just about “their story.” Collaboration and cooperation was required on both sides. Taking the opportunity to build relationships with the reporters during these good news stories will hopefully help me in the future with the bad news or controversial stories. The professional rapport and interchange allowed us to become a little more comfortable with each other and opened the doors for future reporting.

Five lessons I learned in the past week dealing with the media will help me in future news media interactions. This good news story proved to be a perfect event on which to “cut my teeth” in media relations. Hopefully they will help me in future interactions with our news media community partners.

Generational Differences in Training

November 18, 2011

by Roy H. Bethge and Timothy Janowick

Law enforcement has been effected by many of the same changes faced by educational institutions and corporate America when it comes to how we prepare and train for the future. The old model of static lectures without engaging interaction between the student and instructor are no longer effective methods for teaching concepts and skills, especially those involving potential life and death decisions by police officers. It could be argued the changes in instructional style do not revolve around generational differences, rather in the changes all of us have undergone in our lifetime. However, intergenerational conflict presents challenges in the workplace considering the resulting obstructions to progress. Looking at the new models of instructional design with an eye towards generational change makes the idea easier to understand.

What are the Generations?

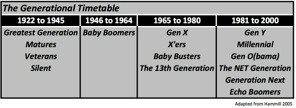

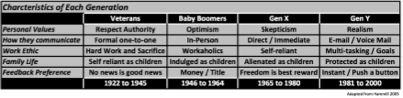

Each generation is shaped by the events, science, and social dynamics present as they grow and mature. The chart below provides an easy reference to help make sense of the four most recent generations and the time periods where they relate. It is important to understand where you fit into the timetable if you truly want to bridge the communication gap that exists between the generations. While not all researchers agree on the beginning and ending birth year of the various generations, Figure 1 provides a basic outline.

Generational Timetable – by Year of Birth (Figure 1)

Now that you know where you fit, spend a few moments thinking about some of the things that have affected you during your lifetime. Think about some of the big moments in history: the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan, the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion, and the death of Princess Diana. If you think these things are not important or significantly relevant to your growing up, consider the following: “When asked to recall how and where Kennedy died, the Veterans and Baby Boomers would say gunshots in Dallas, Texas; Generation X remembers a plane crash near Martha’s Vineyard, Mass; and Generation Y might say, “Kennedy who?” (Hammill 2005). The social, political, and historical events of our youth proved to be formative to whom we are today.

Baby Boomers found themselves affected by the national and global political turmoil of their youth - the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and the assassinations of Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Members of this generation “believe that hard work and sacrifice are the price to pay for success” (Tolbize 2008) whereby paying their dues through excessive hours at work or bringing work home to complete led to a logical progression through promotions. Boomers found work ethic related to self-worth. As masters of their task, Boomers are not interested in constant feedback regarding their work. Chain of command is valued by Boomers, who view skipping supervisors to speak directly with managers as a violation of protocol and disrespectful to the supervisor. As the first generation to experience the technological revolution, Boomers experienced the advent of rotary telephones on walls and sitting on desks, the development of the first computers, and the first to go to power steering.

Generation X grew up in an era of Bill Gates, the advent of the personal computer, and early cellular telephones permanently mounted in vehicles or carried in large black bags. Known for being “latchkey” kids who spent many hours home alone due to dual-income parents or single parents as a result of divorce - they learned to fend for themselves. A product of the latchkey generation is their autonomy and independence, although this does not preclude them from enjoying teamwork - and more so than Boomers. The generation experienced upheaval in politics, the economy, and society. As a result of their experiences in their youth, Xers attempt to create a balance between work and family, and are not found to be overly loyal to their employer as a consequence. Managers have labeled Xers as being slackers, lazy, or uncommitted due to the failure to display fervent loyalty to their employer. Xers value continuous learning,

For many Baby Boomers and Generation X’ers, the current state of innovation remains somewhat foreign, but countless numbers have adapted to the changes beyond their developmental years. As a general statement, adaptation has come about slowly and often, painfully, for many. However, one observation rings true - the Boomers and the X’ers have created organizations catering to their needs, needs often contrary to those of the following generation.

Now lets look at Generation Y who grew up with instant access to information, multiple computers in their homes, and cellular telephones glued to their fingertips. One of the major criticisms heard about Generation Y is that they grew up in a system where they never failed. Awards were given out just for participating in a sport or event regardless of who won or lost. Losing, and thus coping, were not concepts ingrained in them as youths, unlike generations before them. What Generation Y did grow up with was a first hand view of extreme violence. Think Columbine, Virginia Tech, World Trade Center. In contrast to national news coverage of World War II where film reels were sent home via airplane to be broadcast a few days later, Gen Y grew up with the 24-hour news cycle. They watched as the violent events unfolded, live, right before their eyes.

Characteristics of Each Generation (Figure 2)

How does this affect law enforcement training?

Traditional educational systems focus on a structured industrial model of education. Students are divided into classes based on their ages rather than their skill level. The other students in the in class and school represent the same generation. The classroom dynamic of instructing across multiple levels of skill development and methods of learning require law enforcement trainers to become adept in their methodology and technique. It is important to understand generational differences if we hope to create training with a positive impact on improving the skills of our officers and potentially changing the learning culture of law enforcement.

The challenge is increased across the generations as different tactics are employed to engage learners in the process. Boomers may be adverse to team or group activities, while Xers and Gen Y will relish in the experience, preferring group discussion and peer feedback as sources of learning. Supervisors may have witnessed the latter activity as new recruits frequently seek immediate feedback regarding their performance on calls by asking their peers either in person or electronically for an assessment. Xers may also seek independent tasks in the learning environment and focus on learning with fervency, while the youngest members of the workforce can be found using technology to enhance their learning during class.

Although certain strategies in providing instruction may need to be adapted for the differing ages of the learners, adult learners across the board have certain expectations in common: a desire for relevancy to them personally and their work, a need to be addressed, Some simple concepts often applied in instructional design found in corporate America can help law enforcement trainers improve outcomes. In his book Getting Them to Give A Damn (Chester 2005) makes the following recommendations:

•Begin with an orientation, not skills training

•Assess what they know

•Make it fresh

•Keep up the pace

•Reward skills development

While meeting the basic needs of adult learners, trainers must be cognizant of the fact Baby Boomers, X’ers, and Generation Y have embraced advancements in technology from smart phones to digital book readers to computerized gaming. Law enforcement instructors who want to remain on top of their field and make substantial improvements must figure out methods to incorporate this technology into the training environment. Training programs must take on a flair for creativity in design and action rather than the static assembly line of old.

Participants should be challenged in a safe environment and allowed to make mistakes in the training environment. It is only through these mistakes that students can truly learn. Failure in the training environment is correctable. In the real world, failure can be fatal.

Conclusion

Understanding certain key differences between generations can allow for greater success when presenting training to police officers. Although the differing styles may cause trainers to create a careful balance in delivery methods, doing so can allow for the greatest levels of engagement and learning. In recognizing how the generations prefer to receive feedback and at what frequency, trainers will be able to avoid insulting Boomers while ensuring Xers and Gen Y members are not left in angst. The more aware of generation differences an instructor is, the more successful the learning experience can be.

References

Chester, E. Getting Them to Give a Damn. Chicago: Dearborn Trade Publishing, 2005.

Hammill, G. FDU Magazine Online. 2005. http://www.fdu.edu/newspubs/magazine/05ws/generations.htm (accessed October 29, 2011).

Tolbize, Anick. Generational differences in the workplace. Research and Training Center on Community Living, University of Minnesota. 2008.

Completely Unprofessional and Very Reckless

November 13, 2011

By Timothy Janowick

“Completely unprofessional and very reckless,” is Miami Police Sergeant Javier Ortiz' characterization of Florida State Trooper Donna Watts’ conduct in the arrest of Miami Officer Fausto Lopez for speeding at 120 miles per hour in his marked squad car. However, his characterization is incorrect in its application to Trooper Watts. Rather, Officer Lopez proved to be the party acting unprofessionally in his role as a police officer and with great recklessness towards himself, the public, and Trooper Watts.

Particularly disappointing is the number of police officers around the country condoning Officer Lopez’ conduct on October 11 and condemning Trooper Watts for failing to provide Lopez with professional courtesy. Deflecting focus towards the idea of professional courtesy is a defense mechanism to avoid confronting the true issue in this incident - a fellow officer's poor conduct. Lt. Col. Dave Grossman has been known to say, "Denial kills you twice." As you'll soon see, we do quite a bit of killing - of ourselves and innocent individuals - in the midst of our denial.

The question of ethical and professional conduct arising in this situation is certainly worthy of examination and discussion amongst each other, by supervisors in roll call, by administrators determining where their agencies ethical bar rests, and in training where survival tactics are not just about DT and firearms. Additionally, Officer Lopez' driving behaviors are symptomatic of a larger problem in law enforcement when considering our culture and officers' control over reducing line of duty deaths.

A LESSON YET TO BE LEARNED?

What has law enforcement not learned from the driving actions of Illinois State Trooper Matthew Mitchell, who lost control of his 126-mile per hour squad car and killed teenage sisters Kelli and Jessica Schlau? "My daughters were killed by someone who was sworn to protect and serve them," their mother, Kimberly Schlau noted during an interview on the Today show. Is this how we serve our public?

But Trooper Mitchell is not the only law enforcement officer who has killed innocent people in the course of driving recklessly. Trisha Stratman of the LaCrosse County (WI) Sheriff's Department is charged with negligent homicide after allegedly driving through a red light at 90 MPH, killing 16-year Brandon Jennings in July 2010. In 2009, Milford (CT) Police Officer Jason Anderson was accused of killing 19-year-olds David Servin and Ashlie Krakowski while driving 94 MPH during routine patrol. Or Officer Teddie Whitefield of the Wichita Police Department killed 18- and 13-year old cousins as his broadsided their vehicle at 80 miles per hour while on patrol.

Where was the need for these officers to drive at such high rates of speed? What was Officer Lopez' need to drive at 120 MPH while off duty in his marked squad car and risk his life, the life of Trooper Watts, and the lives of the innocent drivers and passengers on the freeway? Where was his respect for his family, his colleagues, and those he is to protect and serve?

The public thrusts a significant trust upon police officers who swear their oath of office. With that oath comes great responsibility to exercise one's conduct on duty and off duty with integrity, respect, and professionalism. Officer Lopez fails to conduct himself with any of these characteristics when he chose to drive with excessive speed. As Trooper Watts conducted her patrol on the highway, Officer Lopez whisked past her marked patrol car with impudence. How can the public expect to take our holding them accountable seriously if we cannot hold ourselves and each other accountable? The integrity of the police officer is eroded through "in your face" conduct violating the law, the public trust, and expectations of professional behavior.

Officer Lopez acted unprofessionally towards the public by driving at an excessive speed through traffic. His lack of professionalism and utterly disrespectful attitude towards the profession is amplified in his failure to stop for Trooper Watts over the 12 miles covered in 7 minutes. In doing so, he demonstrated the ultimate lack of professional courtesy by willingly and flagrantly disobeying the law in the presence of another law enforcement officer, then adding insult by causing Trooper Watts to pursue him. When we err in the presence of each other, we should be quick to respond and acknowledge this to our peers. Forgiveness may come as a professional courtesy provided our actions are not so egregious.

That's right - professional courtesy is not necessarily about "getting a break" when stopped for a traffic violation, but it is more about how we conduct ourselves when in the midst of another police officer. We need to reorient our compass on professional courtesy.

One of the five tenets of the Below 100 campaign focuses on officers' predilection to driving at excessive speeds - whether in response to routine calls, during emergency calls, and in pursuits. We bury more police officers in this country as a result of driving-related factors than those killed feloniously in the line of duty. A majority of those officers would be alive today had they adopted safer driving practices and slowed their speeds. Baltimore Officer Thomas Portz, Jr. died earlier this year after ramming the back of a fire truck; he had been driving 21 MPH over the speed limit during regular patrol.

"We seem to have come to an acceptance on this and this is wrong," Dale Stockton, editor of Law Officer magazine stated when conducting Below 100 Train-the-Trainer program at the ILEETA's conference in April. The statement is a stark truth we must acknowledge and embrace in order to affect change.

In advocating a change to the police culture, Brian Willis challenges us with the question: What's Important Now? Officer Lopez should have considered this powerful question as he raced by traffic at 120 MPH. What's so important about driving at such a reckless speed? What's important about my high speed around all this traffic? What's important now about slowing down so I see my family again? So I meet with my colleague again? So those around me can arrive safely at their destination? What's important now about the trooper behind me signaling me to stop? What's important now about my department's image? My image?

"Why do cops speed? Because they can," the old joke tells us. The time has come to change our behavior - our culture - as police officers. We can't speed and drive without due safe regard for the public, our families, and ourselves. As Chief Jeff Chudwin of Olympia Fields (IL) noted at ILEETA, "Where we go from here will be based on how much we embrace each other."

Completely unprofessional and very reckless? Trooper Watts? Really?

Frankly, the time has come to get over ourselves, to reorient the definition of what professional courtesy really entails, and to become consistent role models to the public we protect and serve.

For more on Below 100, please visit www.below100.com.

Behind the Blue Wall… In the Shadow

October 18, 2011

By Timothy Janowick

The parents waited anxiously in the driveway in the middle of the night as the squad cars arrived, red and blue lights the only illumination of their distraught faces in the darkness. The sergeant shuffled them quickly into the car. As quickly as they appeared, the squads rushed to a local trauma center.

“We had to provide a lights-and-siren escort for a sergeant from a neighboring town last night,” my midnight shift watch commander related. “All we know is an officer had been shot and the sergeant needed to get to the officer’s parents’ house right away.”

A few days later, I stood silently, reverently watching the funeral procession pass on Central Road led by numerous area squad cars, fire engines, and ambulances. A 29-year old officer led to his final resting place. Not the victim of violent action. Not the person in the wrong place at the wrong time of a crash. Not a “traditional” line of duty death. Rather, a young officer dead at his own hand.

He wasn’t the only suburban Chicago officer to commit suicide last week.

Police officers are murdered by felons roughly 70 times every year - by firearms, strangulation, means of terrorism, and by beating. But there is another beating law enforcement officers take, often secreted from the public, hardly ever discussed in training, rarely acknowledged openly by police agencies. It is the dark secret behind the blue wall.

Suicide takes the lives of more law enforcement officers every year than by those intent on murdering an officer. According to the Badge of Life, approximately 145 officers committed suicide in 2010, a rate of 17 suicides per 100,000 officers. The general population suicide rate is 11 per 100,00 people.1 But we don’t really know what the true number is for law enforcement. Some estimate between 350 and 400 officers commit suicide each year. Others commit to a number between 145 and 400.

Unfortunately, because police suicide is more of a secret than an open book, where agencies and officers hide the truth or fail to discuss the realities, we don’t know the exact number. But we do know it is higher than the public at-large.

The nature of the job has the potential to wear on the hearts, minds, and souls of good cops - shift work; being away from family; seeing the bad, the ugly, and the evil of society; improper and inadequate coping strategies (denial, alcohol abuse, extra-marital affairs); and the politics of police organizations can lead a good man or woman down a dangerous path in the absence of proper awareness and support.

Depression can overcome us; suicide can end us and wreak havoc with those who love us. Balance, understanding, compassion, honesty, and action are requisite.

Law enforcement takes great strides to ensure officers are mentally fit when hired - strong warriors in mind, spirit, and physical prowess. Often, we stop after the hiring is complete. Little, if anything, is done to ensure mental and emotional health after a career is moving ahead full steam.

A husband-and-wife, cop-and-social worker, team from Chicago’s western suburbs - Michael Wasilewski and Althea Olson - discussed “Another Cop Killer” in a three-part series on Officer.com.4 “Although there are still vocal and determined opponents of the disease model holding to the vestigial belief that someone who complains of depression is lazy, of weak character and constitution, a malingerer, or even demon-possessed, far more people now see depressive disorders for the serious and debilitating problems they are.” In law enforcement, we need to be here with eyes wide open. Depression is a rarely discussed, often ignored, oppressor.

Some very good law enforcement ambassadors and role models have undertaken a great cause in reducing line of duty deaths for law enforcement officers. Dave “J.D. Buck Savage” Smith promotes the theme, “Not Today!” Officers must adopt this motto, ingrain it in their thoughts during every confrontation, every contact. Dale Stockton and LawOfficer.com are actively engaged in the Below 100 mission to decrease line of duty deaths below 100 for the first time since 1944, particularly through areas where officers have control: strapping on a seatbelt, reducing speed, wearing a vest, avoiding complacency, and asking “What’s Important Now?”2

We are educating officers about the control they have in preventing their deaths in the line of duty. These are not the only areas where officers have control of their outcome in the performance of their duty.

We need to broaden the scope of action aimed at lowering the number of deaths of law enforcement officers and include reducing suicides, particularly when we do more harm to ourselves than the bad guys do. It’s time to step out from the shadows of our walls.

Wasilewski and Olson ask tough questions: “Will you be able to see [depression] so clearly if it hits a colleague, a friend, or even yourself? Will you know what to do then?”

Education and awareness are essential to curbing the impact of a tough job and the damage done unto ourselves, just as it is through Below 100’s endeavor to reduce line of duty deaths.

Agencies should develop peer support teams and critical incident stress debriefing teams. Depression and suicide awareness training must become incorporated in our training. Cultural change must incorporate open and frank discussion identifying where organizational culture increases risk, how to recognize destructive behaviors, and the means to conduct interventions.

In his article, “Below 100 - Be The Change,” Brian Willis challenges us to stop making excuses: “As I speak to law enforcement professionals around North America, I continually hear people start a sentence—an excuse, really—with the words “I’m just a…” I’m just a patrol officer, I’m just a corporal, I’m just a sergeant, I’m just a Lieutenant, etc. What follows is an excuse why they can’t make a difference in their organization, an excuse why they’re somehow not responsible for effecting a change in the culture of their organizations.“3

What good excuse is there, really?

Action requires the currency of courage, responsibility, and accountability. Courage to speak openly, to ask the tough question, to involve the families. Responsibility for ourselves - how we choose to react, to engage in our own emotional self-care, to cope with the challenges of policing, to ask for help. Accountability to and for each other - ask a buddy how he’s doing, listen to telltale language, notice the behavioral changes, act when we recognize depression.

Today’s challenge is to say “Not Today” to it all - accidents, inattentiveness, short-cuts, miscalculated or inappropriate bravado, carelessness, depression, and death by our own hands.

We are the force for change - in ourselves and in our agencies. Winning - on the street or in our souls - is not an option.

Be the change. Bring light where there is darkness.

1 “Badge of Life, a national police suicide prevention group noted its credibility, has announced its figures on police suicides during 2010.” <<http://www.policesuicideprevention.com/id48.html>>

2 Stockton, Dale. “Below 100 - Introduction.” Officer.com. October 20, 2010. Accessed at: <<http://www.lawofficer.com/article/below-100/below-100>>

3 Willis, Brian, “Be The Change.” LawOfficer.com. August 23, 2011. Accessed at: <<http://www.lawofficer.com/article/below-100/below-100-be-change>>

4 Wasilewski, Michael and Olson, Althea. “Another Cop Killer.” Officer.com. 08 April 2011. Accessed at: <<http://www.officer.com/article/10233345/another-cop-killer>>

See also:

Wasilewski, Michael and Olson, Althea. “Another Cop Killer, Part 2.” Officer.com.

Nice Try, But... Off-the-Mark Leadership

You don’t need to keep hitting people over the head - that’s assault, not leadership.

-Dwight D. Eisenhower

Perhaps you have heard the phrase, “unintended consequences of well-intentioned people.” Unfortunately, leaders can fall into the trap of unexpected outcomes due to a lack of self-awareness and understanding of emotional intelligence in attempting to demonstrate leadership by doing subordinates’ jobs with them (or for them).

Leaders are expected to to hold a number of positive qualities, for those qualities are the conduit a leader utilizes to convey a mission and motivate people to follow. People want a leader who is mix of a visionary, manager, coach, change agent, teacher, and decision maker. Balance in each of these qualities is important for achieving success. Leaning too heavily on a quality or failing to bring enough to the table can be problematic. When managing, too much can be a bad thing.

Empowering people to do their jobs, encouraging performance with maximum effort, and producing meaningful results are expected actions of leaders. Empowerment allows people to lead in their area of expertise or responsibility, or what Joseph Raelin refers to a being “leaderful.” Encouragement is the process of offering emotional and tangible support to do the job. The end product, if all comes together properly, will produce meaningful results - for the company in terms of recognition, profit, and successful goal achievement and for the people involved in a project who garner pride, self-esteem, respect, and satisfaction through their involvement.

Sometimes, though, leaders become overzealous in their involvement with those they lead as they attempt to lead from the front by actively participating in the details of a project or assignment with team members or employees instead of managing the big picture.

While the motivation for such leadership action can be pure and with good intention to “be a part of the team,” the action of direct participation by helping others perform their jobs and tasks comes across with negative messages - and consequences - from good intentions. The leader’s actions will be perceived as lacking trust in the employee or team member to do the job correctly (or do it at all), the leader perceives the employee as lazy or incapable, or a micromanagement of details is being undertaken. The result is repeated blows to workers or team members who experience fading morale, decreasing self-esteem, reduced or eliminated satisfaction, and loss of respect for the leader.

Emotional intelligence requires leaders to be cognizant of the impact of their actions when participating with employees to avoid assaulting egos and self-esteem. Developing leaderful people requires more distance than hovering.

As a leader, take the time to step back and assess your involvement in tasks or jobs performed by subordinates. If you find yourself doing the jobs of those who follow you, stop and step back. You’ll be surprised at how much healthier and fuller the results will be - in your project and the people you lead.

In Honor, Memory, and Thanksgiving for the Lions

Early afternoon thunderstorms passed and rays of warm sunshine broke through the clouds as I approached the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial for the first time more than a decade ago. Taken by the awe of the experience, I tried to soak in as much as I could - the mementos, letters. articles, artifacts, and the clutching embraces of family and friends amidst the throngs of police officers.

While walking the Pathway of Remembrance, I came across a woman holding an infant in one arm and the hand of a boy about 4 years of age with her other hand. The children were about the same age as mine at the time. The little guy repeated asked to see his daddy. Without hesitation she released his hand and told him to go say hello to his daddy.

I stepped back to allow the boy to pass and expecting one of the men around me to embrace the child. Instead, I watched as the boy walked up to the memorial wall and gently stroked a picture of his father’s face. “Hello, Daddy, hello. I love you,” he repeated several times. His father was murdered in the prior year.

My heart sank; my eyes welled. The true impact of this officer’s sacrifice became readily apparent.

Today is National Peace Officers Memorial Day, in honor of the more than 19,000 law enforcement officers who have given the most any one man or woman can give to their friends, neighbors, and community - they have given their lives.

As we gather together in our houses of worship, enjoy the spring warmth with friends and family, or work a beat on the street, let us take a moment to honor the memory of these community heroes and give thanksgiving for the lions who provide service and protection to our communities. Fly flags at half-staff today in honor as directed by the President.

Without our community guardians - the warriors who protect when all else run, we could not enjoy the freedoms and lives we enjoy today.

In a time where danger lurks ever more present for police officers, we can make an impact and work to reduce the number of officers killed each year. We have a duty to those who have sacrificed to learn and improve to avoid the same fate.

Below 100 is a program initiated by LawOfficer.com to bring awareness to five simple actions to take to reduce the risk of dying while serving: vest up, buckle up, watch your speed, avoid complacency, and ask ‘What’s Important Now?’ No time exists more so than the present to learn more and initiate action by looking at http://www.lawofficer.com/below100.

Do this to honor the memories of our brothers and sisters who have made the greatest sacrifice.

Trainer, You Are A Leader

May 8, 2011

Roy Bethge and Tim Janowick

Of all the descriptions ascribed to trainers, maybe the most important is leader. Regardless of rank or title, when it comes to your training event you are in charge. Are you ready to step up and accept this challenge?

Creating adult training requires considerable work to be effective. As the trainer, you are responsible for researching emerging trends and ensuring your content is current and relevant.

Adult learners expect leaders at the front of the classroom. Credibility for you and your topic are critical. For in-house instruction, the applicable phrase is “organizational credibility.” This provides unique challenges because many of your students know you personally. They know your strengths, weaknesses and most frighteningly, mistakes. When teaching for another institution or speaking at a seminar, instructor acceptance falls upon experience, presentation quality, and engagement. Do these ideas sound a lot like leadership?

Great trainers, like great leaders, do it from the front. Leader-educators facilitate learning and relationship establishment between the adult learner and the material by being willing to put others before self. Possessing a unique and strong ability to communicate visions and ideas, trainers move agencies forward. Again, aren’t these the same expectations we set for our leaders?

We can demonstrate our leadership skills in many ways. However, leading by example or through how we live our lives and perform our jobs is most important. Leaders take risks, are willing to make difficult decisions, and aren’t afraid to fail forward.

Step forward to do what’s right for the students, agency, and profession, regardless of whether it’s popular or not. Be a leader in everything that you do, your life and the lives of officers you train may depend on it.

This article appears in the May 2011 ILEETA Digest.